Well by design: stop treating people like cogs in a machine

In the debate about better wellbeing solving the productivity crisis, could greater employee participation in workplace design be an answer? A new study suggests it can

A decade after the great financial crash of 2008, the global workplace is still struggling with sluggish rates of productivity. Putting the wheels back on the wagon after they came off in such disastrous fashion is clearly proving to be a difficult job.

Investment in training, infrastructure and other support has failed so far to bridge the performance gap, which is why workplace design itself is now under the microscope. But for workplace design to really influence today’s productivity debate, two big paradigm shifts need to be recognised. Both relate to employee wellbeing and control.

Away from efficiency

The first shift is stop talking about efficiency metrics in a way that treats people as cogs in a machine – and organisations as giant pieces of engineering that only need their bolts to be tightened. Better by far to start talking about workplace experience and wellbeing as a soft route to higher levels of productivity: a happier, more engaged workforce is more likely to do better work. Workplace designers are comfortable with this angle and are already talking this game.

The second shift is harder for the design professionals to swallow. This is to accept that conventional design projects briefed by the most senior managers with minimal employee input in the lower ranks may produce less productive workplaces than schemes that involve an element of co-design with the people who will work in the space.

‘Participatory design featured less in office buildings compared to other design areas…’

Participatory design has been less of a feature in office buildings compared to other design areas such as consumer electronics or community architecture, but this could be about to change. The catalyst: a ‘wellbeing deficit’ at work that requires urgent attention en route to improving productivity.

While there are less direct physical and ergonomic threats to health in today’s workplace, compared to when a large proportion of the workforce toiled in factories or mines, there has been a dramatic rise in mental health issues related to stress, depression, anxiety and burnout.

So the big underlying challenge is psychological wellbeing at work. For designers long skilled in improving functional comfort – making a workplace fit for purpose – this is new territory. It involves designing for trust, identity, loyalty, empowerment, self-esteem and, above all, personal control. If you study the scientific literature around personal wellbeing, the term ‘sense of control’ crops up repeatedly.

Participation and wellbeing studied

In a research study jointly led by the Royal College of Art and architects Gensler with industry partners Milliken, Kinnarps, Bupa and RBS, we set out to see whether giving people greater participation in the design of their work environment – a design-based sense of control – could boost wellbeing.

Giving employees a choice to participate in design can help employee wellbeing

What we learnt was surprising. After an initial scoping study in four different organisations in London and the south-east to identify the key design factors that influence wellbeing, we set up an experiment with three employee teams in one organisation to test the impact of different levels of design participation (high, low and no participation) on personal wellbeing.

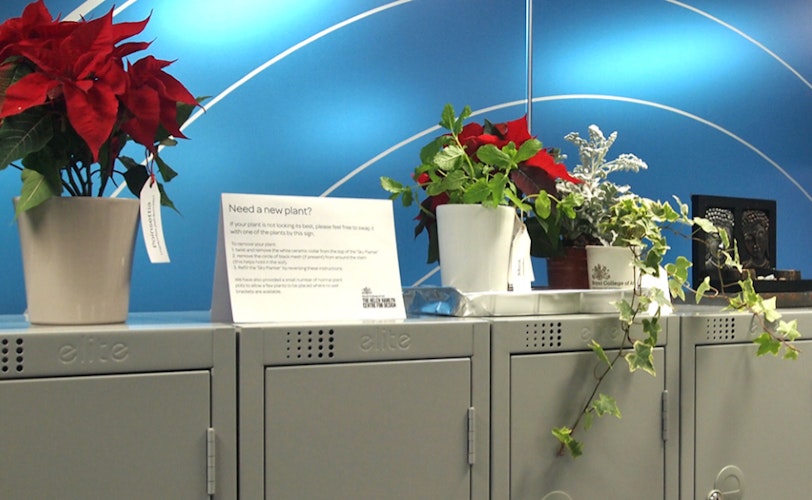

The three teams worked with the researchers to co-design interventions in their workspace. A validated measurement of mental wellbeing, the Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale, was used to measure the effects on employees.

Giving people a voice

The results found that while teams that were given a role in the design of the environment recorded a rise in mental wellbeing compared to the no-participation team, there was hardly any difference in the level of wellbeing between low and high participation. The invitation to participate was seen as more important to wellbeing than the level or ‘dose’ of participatory activity offered.

This has implications for how participation is managed and wellbeing is addressed through workplace design. Could it be that – contrary to many expert views – giving a lot of people right across the organisation some say in the design for their environment, however small, is more beneficial to employee wellbeing than working with a single, handpicked expert employee group?

‘Developing a practical evaluation toolkit for organisations…’

Our study went on to develop a conceptual model for wellbeing that seeks a balance between the functional and psychological needs of the individual, and then a practical evaluation toolkit for organisations to use to measure workplace wellbeing and activate design to improve it.

The toolkit enables companies to analyse the functional and psychological needs of their employees, map the results on a wellbeing matrix, identify design opportunities for improvement and co-create solutions. It provides a platform for understanding how recalibrating aspects of workplace design can address the wellbeing deficit.

While such an approach is unlikely to be a quick fix for the productivity malaise that the UK and other advanced economies currently face, it nevertheless provides a basis for engaging the workforce with their environment – and learning more about the dynamic links between workplace design and wellbeing.

Join the conversation

The Royal College of Art-Gensler research report is called Workplace & Wellbeing: Developing a practical framework for workplace design to affect wellbeing.

To hear a Monocle radio interview with WORKTECH Academy director Jeremy Myerson, who led the study, click here.

To watch a video of a London roundtable on wellness in the workplace held at research partner Milliken as part of Clerkenwell Design Week 201, chaired by Jeremy Myerson, click here.